From the foreword:

These poems are the very essence of the British spirit. They are, to

literature, what the bloom of the heather is to the Scot, and the

smell of the sea to the Englishman. All that is beautiful in the old

word “patriotism” … a word which, of late, has been twisted to such

ignoble purposes … is latent in these gay and full-blooded measures.

But it is not only for these reasons that they are so valuable to the

modern spirit. It is rather for their tonic qualities that they should

be prescribed in 1934. The post-war vintage of poetry is the thinnest

and the most watery that England has ever produced. But here, in these

ballads, are great draughts of poetry which have lost none of their

sparkle and none of their bouquet.

It is worth while asking ourselves why this should be–why these poems

should “keep”, apparently for ever, when the average modern poem turns

sour overnight. And though all generalizations are dangerous I believe

there is one which explains our problem, a very simple one…. namely,

that the eyes of the old ballad-singers were turned outwards, while the

eyes of the modern lyric-writer are turned inwards.

The authors of the old ballads wrote when the world was young, and

infinitely exciting, when nobody knew what mystery might not lie on the

other side of the hill, when the moon was a golden lamp, lit by a

personal God, when giants and monsters stalked, without the slightest

doubt, in the valleys over the river. In such a world, what could a man

do but stare about him, with bright eyes, searching the horizon, while

his heart beat fast in the rhythm of a song?

But now–the mysteries have gone. We know, all too well, what lies on

the other side of the hill. The scientists have long ago puffed out,

scornfully, the golden lamp of the night … leaving us in the uttermost

darkness. The giants and the monsters have either skulked away or have

been tamed, and are engaged in writing their memoirs for the popular

press. And so, in a world where everything is known (and nothing

understood), the modern lyric-writer wearily averts his eyes, and stares

into his own heart.

That way madness lies. All madmen are ferocious egotists, and so are all

modern lyric-writers. That is the first and most vital difference

between these ballads and their modern counterparts. The old

ballad-singers hardly ever used the first person singular. The modern

lyric-writer hardly ever uses anything else.

This is really such an important point that it is worth labouring.

Why is ballad-making a lost art? That it is a lost art there can

be no question. Nobody who is painfully acquainted with the rambling,

egotistical pieces of dreary versification, passing for modern

“ballads”, will deny it.

Ballad-making is a lost art for a very simple reason. Which is, that we

are all, nowadays, too sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought to

receive emotions directly, without self-consciousness. If we are

wounded, we are no longer able to sing a song about a clean sword, and a

great cause, and a black enemy, and a waving flag. No–we must needs go

into long descriptions of our pain, and abstruse calculations about its

effect upon our souls.

It is not “we” who have changed. It is life that has changed. “We” are

still men, with the same legs, arms and eyes as our ancestors. But life

has so twisted things that there are no longer any clean swords nor

great causes, nor black enemies. And the flags do not know which way to

flutter, so contrary are the winds of the modern world. All is doubt.

And doubt’s colour is grey.

Grey is no colour for a ballad. Ballads are woven from stuff of

primitive hue … the red blood gushing, the gold sun shining, the green

grass growing, the white snow falling. Never will you find grey in a

ballad. You will find the black of the night and the raven’s wing,

and the silver of a thousand stars. You will find the blue of many

summer skies. But you will not find grey.

That is why ballad-making is a lost art. Or almost a lost art. For even

in this odd and musty world of phantoms which we call the twentieth

century, there are times when a man finds himself in a certain place at

a certain hour and something happens to him which takes him out of

himself. And a song is born, simply and sweetly, a song which other

men can sing, for all time, and forget themselves.

Contents:

Foreword

Mandalay

The Frolicksome Duke

The Knight and Shepherd’s Daughter

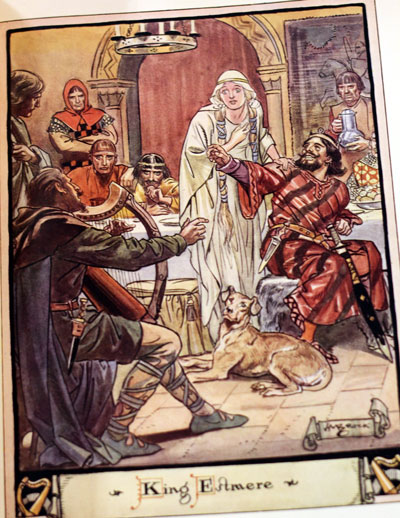

King Estmere

King John and the Abbot of Canterbury

Barbara Allen’s Cruelty

Fair Rosamond

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne

The Boy and the Mantle

The Heir of Linne

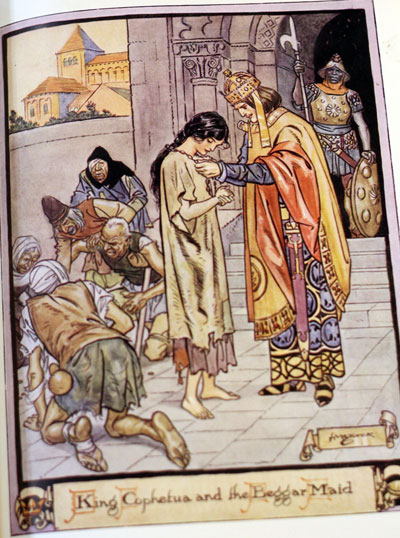

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid

Sir Andrew Barton

May Collin

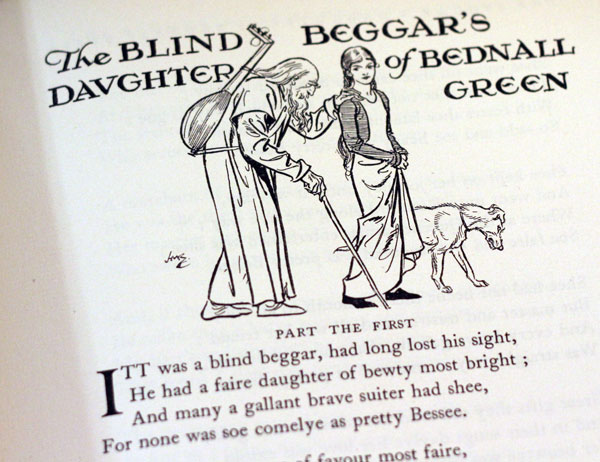

The Blind Beggar’s Daughter of Bednall Green

Thomas the Rhymer

Young Beichan

Brave Lord Willoughbey

The Spanish Lady’s Love

The Friar of Orders Gray

Clerk Colvill

Sir Aldingar

Edom O’ Gordon

Chevy Chace

Sir Lancelot Du Lake

Gil Morrice

The Child of Elle

Child Waters

King Edward Iv and the Tanner of Tamworth

Sir Patrick Spens

The Earl of Mar’s Daughter

Edward, Edward

King Leir and His Three Daughters

Hynd Horn

John Brown’s Body

Tipperary

The Bailiff’s Daughter of Islington

The Three Ravens

The Gaberlunzie Man

The Wife of Usher’s Well

The Lye

The Ballad of Reading Gaol