About the book:

Also known as Japan, Madame Chrysanthème is an autobiographical account by Pierre Loti describing how he took a temporary Japanese wife. Below is the blurb from Goodreads – the officer in question in the blurb is Loti himself.

From Goodreads:

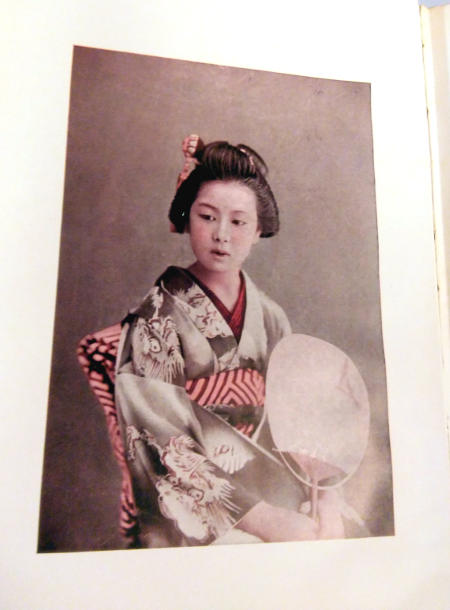

Pierre Loti’s novel Madame Chrysanthème (1888) enjoyed great popularity during the author’s lifetime, served as a source of Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, and remains in print to this day as a classic in Western literature. Loti’s story, cast in the form of his fictionalized diary, describes the affair between a French naval officer and Chrysanthème, a temporary “bride” purchased in Nagasaki. More broadly, Loti’s novel helped define the terms in which Occidentals perceived Japan as delicate, feminine, and, to use one of Loti’s favorite words, “preposterous”—in short, ripe for exploitation.

About Pierre Loti (from Wikipedia):

Born to a Protestant family, Loti’s education began in his birthplace, Rochefort, Charente-Maritime. At age 17 he entered the naval school in Brest and studied at Le Borda. He gradually rose in his profession, attaining the rank of captain in 1906. In January 1910 he went on the reserve list. He was in the habit of claiming that he never read books, saying to the Académie française on the day of his introduction (7 April 1892), “Loti ne sait pas lire” (“Loti doesn’t know how to read”), but testimony from friends proves otherwise, as does his library, much of which is preserved in his house in Rochefort. In 1876 fellow naval officers persuaded him to turn into a novel passages in his diary dealing with some curious experiences at Constantinople. The result was the anonymously published Aziyadé (1879), part romance, part autobiography, like the work of his admirer, Marcel Proust, after him.

In 1887 he brought out a volume “of extraordinary merit, which has not received the attention it deserves”, Propos d’exil, a series of short studies of exotic places, in his characteristic semi-autobiographic style. Madame Chrysanthème, a novel of Japanese manners that is a precursor to Madama Butterfly and Miss Saigon (a combination of narrative and travelog) was published the same year.

n 1899 and 1900 Loti visited British India, with the view of describing what he saw; the result appeared in 1903 in L’Inde (sans les anglais) India (without the English). During the autumn of 1900 he went to China as part of the international expedition sent to combat the Boxer Rebellion. He described what he saw there after the siege of Peking in Les Derniers Jours de Pékin (The Last Days of Peking, 1902).

Pierre Loti visited Istanbul many times, firstly in 1876 as an officer on a French ship. Loti was deeply affected by Ottoman life style and this was reflected in his novels. There he met the woman who supposedly inspired the novel Aziyadé. He lived in Eyüp during his time in Istanbul. He always qualified himself as a friend of Turks. In his 1913 book Turquie Agonisante (Turkey in Agony), he criticized Western attitudes toward the Ottoman Empire. The same year he went to Turkey as a guest of the state and was welcomed with a grand ceremony on Tophane Quay. Sultan Reşat hosted him in his palace. During the Balkan Wars, World War I and afterwards, he always defended the Turks against Europe in the occupation of Anatolia. By his support to resistance in Anatolia and his critics against his own country, he gained the sympathy of the Turkish people. In response to Pierre Loti’s support for the Turkish War of Independence, the Council of Ministers sent him a message of gratitude. He was accepted as an Istanbul City Honorary Citizen in 1920, and a community was named after him.[8] An avenue in the Binbirdirek district (Piyer Loti Caddesi) and a coffeehouse in Eyüp are named after him. Today the hill known as Pierre Loti Hill (Pierre Loti Tepesi) in Istanbul derives from this coffeehouse.