About Li Hung Chang (from Wikipedia):

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi (Li Hung-chang; 15 February 1823 – 7 November 1901) was a Chinese politician, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in important positions in the Qing imperial court, including the Viceroy of Zhili, Huguang and Liangguang.

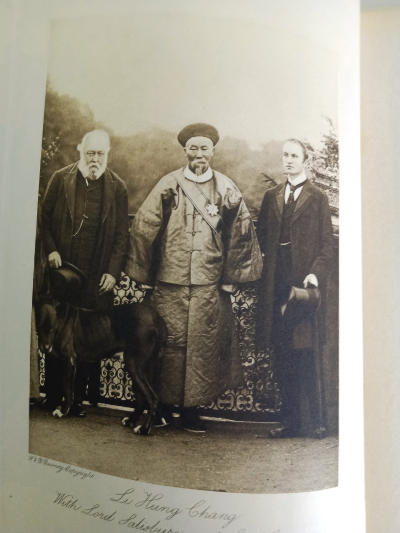

Although he was best known in the West for his generally pro-modern stance and importance as a negotiator, Li antagonised the British with his support of Russia as a foil against Japanese expansionism in Manchuria and fell from favour with the Chinese after their defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War. His image in China remains controversial, with criticism on one hand for political and military defeats and praise on the other for his success against the Taiping Rebellion, his diplomatic skills defending Chinese interests in the era of unequal treaties, and his role pioneering China’s industrial and military modernisation. He was presented the Royal Victorian Order by Queen Victoria. The French newspaper Le Siècle described him as “the yellow Bismarck.”

In 1860, Li was put in command in the naval forces in Anhui and Jiangsu provinces to counter the Taiping rebels. After Zeng Guofan’s Xiang Army recaptured Anqing from the rebels in 1861, Zeng wrote a memorial to the imperial court to praise Li, calling him “a talent with great potential”, and sent Li back to Hefei to form a militia. Li managed to recruit enough men to form five battalions in 1862. Zeng Guofan ordered him to bring his troops along with him to Shanghai. Li and his men sailed past rebel-controlled territory along the Yangtze River in British steamboats – the rebels did not attack because Britain was a neutral party – and arrived in Shanghai, where they were commissioned as the Huai Army. Zeng Guofan recommended Li to serve as the xunfu of Jiangsu Province. After gaining ground in Jiangsu, Li focused on enhancing the Huai Army’s capabilities, including equipping them with Western firearms and artillery. Within two years, the Huai Army’s strength increased from 6,000 to about 60–70,000 men. Li’s Huai Army combined forces later with Zeng Guofan’s Xiang Army and Charles George Gordon’s Ever Victorious Army and prepared to attack the Taiping rebels.

After the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion in 1864, Li assumed a civil office as the xunfu of Jiangsu Province for about two years. However, on the outbreak of the Nian Rebellion in Henan and Shandong provinces in 1866, he was ordered to lead troops into battle again. After some misadventures, Li managed to suppress the movement. In recognition of his contributions, he was appointed as Assistant Grand Secretary (協辦大學士).

In 1886, on the conclusion of the Sino-French War, Li arranged a treaty with the French. Li was impressed with the necessity of strengthening the Qing Empire, and while he was Viceroy of Zhili, he raised a large well-drilled and well-armed force, and spent vast sums both in fortifying Port Arthur and the Dagu forts and in strengthening the navy. For years, he had watched the successful reforms effected in Japan and had a well-founded dread of coming into conflict with the Japanese.

In 1900, Li once more played a major diplomatic role in negotiating a settlement with the Eight-Nation Alliance forces which had invaded Beijing to put down the Boxer Rebellion. His early position was that the Qing Empire was making a mistake by supporting the Boxers against the foreign powers. During the Siege of the International Legations, Sheng Xuanhuai and other provincial officials suggested that the Qing imperial court give Li full diplomatic power to negotiate with foreign powers. Li telegraphed back to Sheng Xuanhuai on 25 June, describing the declaration of war a “false edict”. This tactic gave the “Southeast Mutual Protection” provincial officials a justification not to follow Empress Dowager Cixi’s declaration of war. Li refused to accept orders from the government for more troops when they were needed to fight against the foreigners, which he had available. Li controlled the Chinese telegraph service, whose despatches asserted falsely that Chinese forces had exterminated all foreigners in the siege and convinced many foreign readers.

In 1901, Li was the principal Chinese negotiator with the foreign powers which captured Beijing. On 7 September 1901, he signed the Boxer Protocol ending the Boxer Rebellion, and obtained the departure of the Eight-Nation Alliance at the price of huge indemnities for the Chinese. Exhausted from the negotiations, he died from liver inflammation two months later at Xianliang Temple in Beijing. The Guangxu Emperor posthumously honoured Li as Marquis Suyi of the First Class (一等肅毅候). This peerage was inherited by Li Guojie, who was assassinated in Shanghai on 21 February 1939, allegedly as a result of his support for the Nanking Reformed Government