About the Author (from wikipedia):

Sir Robert Hamilton (“R.H.”) Bruce Lockhart, KCMG (1887 – 1970), was a British diplomat (Moscow, Prague), journalist, author, secret agent and footballer. His 1932 book, Memoirs of a British Agent, became an international best-seller, and brought him to the world’s attention.

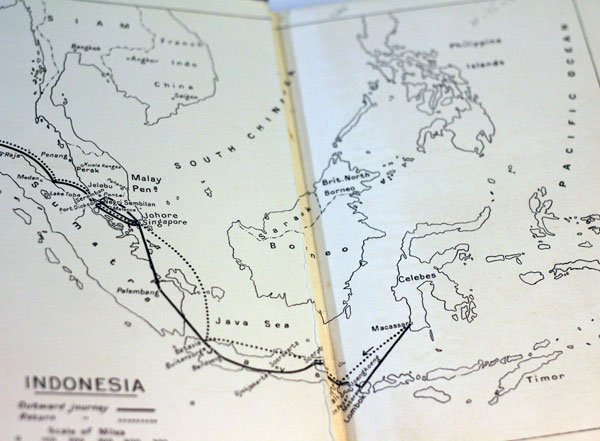

At age 21, he went out to Malaya to join two uncles who were rubber planters there. According to his own account, he was sent to open up a new rubber estate near Pantai in Negeri Sembilan, in a district where “there were no other white men”. He then “caused a minor sensation by carrying off Amai, the beautiful ward of the Dato’ Klana, the local Malay prince… my first romance”. However, three years in Malaya, and one with Amai, came to an end when “…doctors pronounced Malaria, but there were many people who said that I had been poisoned”. One of his uncles and one of his cousins “bundled my emaciated body into a motor car and… packed me off home via Japan and America”. The Dato’ Klana in question was the chief of Sungei Ujong, the most important of the Nine States of Negeri Sembilan, whose palace was at Ampangan.

Review from The Tablet, a Catholic news weekly, from 1936:

The feeling of the East is as subtle and as difficult to evoke as the sensation of sight and smell. The heat, the insects, the colour of earth and sky, of sunsets, of natives and butterflies ; the violent contrasts between light and shade ; the wild and rambling expansion of trees and flowers ; and a thousand other things enter into the mechanism of the East sensation, not merely building a different world, but creating a twin personality in the onlooker, which dies out again in the West and revives in the East. The itch to recall it drove, as it has driven many others, R. H. Bruce Lockhart back to that East which swelters under the leaden skies of Malaya, Sumatra and Java, and to write about it.

The pleasure was for himself, but his art is for his readers, and of these only lovers of the East can test how far the writer has been able to revive the sensations of that other world : all its materials are there, not merely recorded, but embedded in the experiences of a traveller who moves at a quick pace, with light equipment, a curious eye and a facile pen.

Twenty years have wrought a great change in the East, where education, the Great War, and the pressure of populations have set up the usual ferment that looses the old bonds of social custom and political submission. Japan has effected her first entry into the rich colonies of the Dutch by her cheap and alluring wares ; the islanders themselves have grown conscious of their racial and national identity ; British and Dutch are watching the change with anxiety, and Mr. Lockhart has the exact measure of loyalty and sympathy to record it with fairness to both rulers and subjects. In an interview the Dutch Governor-General rose from his chair and taking a ruler, pointed to a place on the map. ” That ‘s where Siam will one day cede territory for a canal to Japan or build it herself with Japanese money,” he said, “and then good-bye to Singapore.” The place to which he pointed was Kra, the isthmus situated in Siamese territory at the narrowest point of the long Malay peninsula, about eight hundred miles north of Singapore ! What a vista of possibilities ! It is like opening a new window on the East.

In British Malaya the writer sees a danger, which has been obvious to many observers and not only in the British Empire, in the speeding-up of administration. “It puts a premium on yes-men and destroys initiative. . . . The canker in the body politic of all empires is want of spirit and lack of direction of intention. The decline of the Roman Empire began when the civil servants of Rome started to suppress every symptom of energy, initiative and enterprise shown by the local administrators.”

But the speeding-up goes further, for it is well known that the motor car has all but completely severed the civil service from the colonial populations : officials rush about the country in their cars, expect short answers to short inquiries, and the native replies in disgust that “All is well.” Those natives who still remember the old civil servant, patient, interested, listening to all their woes, and staying overnight in the village, shake their heads, as though the British Empire had come to an end.

Mr. Lockhart is a frank admirer of the Dutch civil servant : “The Fax Batavia is in some ways a more remarkable achievement than even the Fax Britannica,” for it is more elastic, more understanding and, however firm, more sympathetic to the natives; • and he suggests that the Malayan civil servants should be made to travel over Dutch India as part of their training, though it is just as likely that the Dutch would discover things to learn in the British Empire.