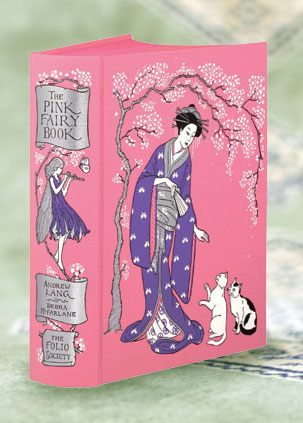

Title: The Pink Fairy Book

Author: Andrew Lang, A. S. Byatt (intro), Debra McFarlane (illus)

ISBN: –

Publisher: The Folio Society, 2003

Condition: New and perfect. Bound in cloth, blocked with a design by Debra McFarlane. 352 pages with decorative embellishments; frontispiece and 12 full-page colour illustrations. Book Size: 10” × 7½”.

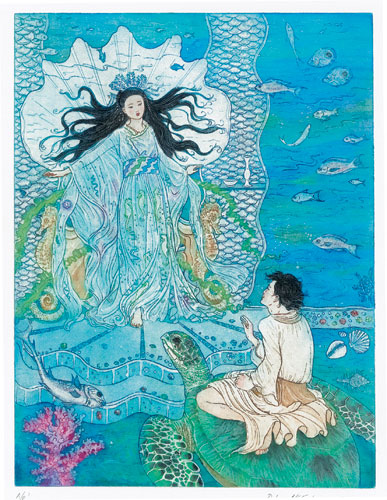

‘He hid the box safely in his garments, seated himself on the back of the turtle, and vanished in the ocean path, waving his hand to the princess’

FROM URASCHMATARO AND THE TURTLE

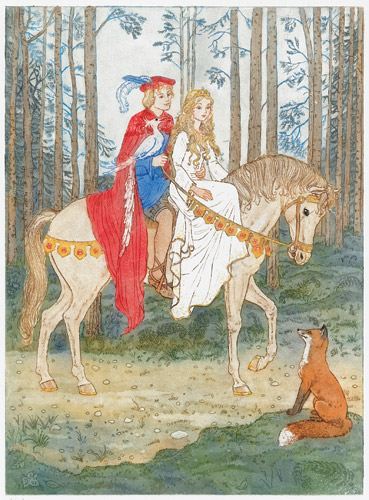

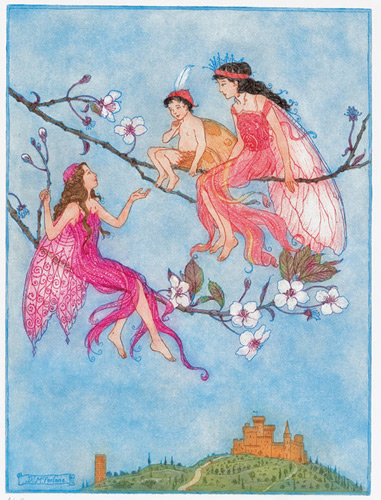

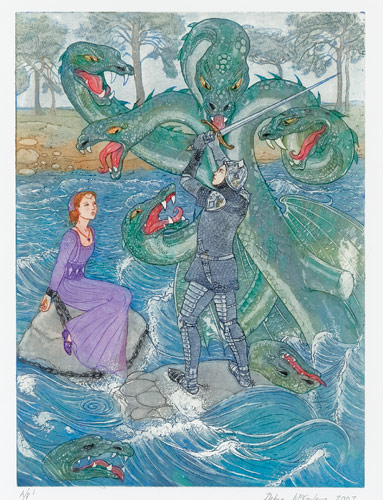

In these tales third-born sons seek their fortunes, lovely princesses are blown away by gusts of wind, cunning tricksters steal treasures from dragons, wicked wizards chase after their apprentices, and wise animals help their friends…

Andrew Lang was famous for his ‘Rainbow Fairy Books’ and generations of children including our introducer, the novelist A. S. Byatt, grew up reading these enchanting, and occasionally disturbing, stories. For The Pink Fairy Book, Lang drew upon a range of cultures and traditions, bringing together 41 stories from Japan, Scandinavia, Africa, Sicily and Catalonia, as well as enduring favourites including ‘The Snow Queen’ by Hans Christian Andersen and ‘The House in the Wood’ by the Brothers Grimm. Many had never appeared in any English collection before and Lang had them translated and sympathetically retold. Here, gruesome stories (a princess possessed by a demon devours her guards) have their place alongside unashamedly comic ones (three merry wives play tricks on their husbands to determine which is the most stupid) and an occasional tragic tale (the little, much-loved snow child melts away in the fire’s heat).

Debra McFarlane has produced dozens of lovely pen-and-ink drawings for these stories as well as 13 full-page colour paintings. In her whimsical and delicate artworks, fairies flit mischievously through the air, woodland animals prick up their ears and beautiful maidens catch the eyes of handsome boys. This is a gorgeous edition to treasure, whether you are introducing children to these ancient and compelling stories, or rediscovering for yourself their many pleasures and hidden meanings.

‘An eclectic collection like this is such a pleasure to read’

A. S. BYATT

The Forms of the Fairy Tale

A.S. Byatt, renowned literary critic and Booker Prize–winning novelist, explores how the unique characteristics of the fairy tale are revealed in Andrew Lang’s collection of authored and anonymous tales in The Pink Fairy Book.

ANDREW LANG in his preface to The Pink Fairy Book raises the question of frightening children, with reference to the Danish tale he includes, ‘The Princess in the Chest’. The Pink Fairy Book is not a strict collection of folk–tales, or Märchen. It includes authored tales, three by Hans Andersen, including ‘The Snow Queen’, one of the greatest stories ever written, and the fanciful ‘Princess Minon–Minette’ from the Bibliothèque des Fées et des Génies. The stories are an eclectic mixture in other ways – there are tales from Africa and Japan, as well as from northern and southern Europe. Tales are translated from translations – the Sicilian story is translated from a German translation, the African tales are translated from the French. Hans Andersen himself is translated not from Danish but from the German, as was usual in Victorian England – recent work on the translations suggests that he was smoothed and sentimentalised as the translations succeeded each other. The translation of the Sicilian story – ‘Catherine and Her Destiny’ – may, I think, disguise the fact that the Italian word for what we call fairies or elves is Fata – a Mediterranean kind of spirit who is both fairy and fate. Lang employed many translators, including his wife. It resulted in the stories changing shape in transmission as stories do.

But in the case of ‘The Princess in the Chest’ Lang thought it worthwhile to explain some changes he had made to the Danish tale – which, he says, ‘need not be read to a very nervous child, as it rather borders on a ghost story. It has been altered, and is really much more horrid in the language of the Danes, who, as history tells us, were not a nervous or timid people.’ The distinction between ghost story – designed to arouse fear and anxiety – and fairy tale is interesting. Danish friends sent me a text of the original and translated the ending, whose omission seems to be the striking difference in Lang’s version. Lang ends with a wedding and happiness ever after. The original ending reads:

‘But many years later, when all the tiles in the church had to be relaid, a loose stone was found in the middle of the floor. Beneath, a huge vault was found in which lay the bodies of the sentries who had watched the coffin of the princess. Each neck had been broken. This was the work of the evil being who had possessed the princess, and had drunk three drops of their blood every night.’

Lang is right – this vampiric shiver is stronger than a fairy–tale emotion, and the suggestion of a possessing evil being is a motif that belongs more to a ghost or horror story than to a fairy tale. Hans Andersen creates the same shiver with a bewitched and evil princess in ‘The Travelling Companion’.

Andersen’s tales do and don’t resemble the forms of the traditional fairy tale. He understands these forms from the inside, but he does not restrict himself to depthlessness, abstract style or isolation. Indeed, I believe he was the first writer to invent the form of tale in which inanimate objects – darning needles, bits of broken glass, or, in the ones included in The Pink Fairy Book, a conceited shirt–collar, a flirtatious garter and a dancing pair of scissors. All have more personality than they can manage, and are comic and tragic by turns.

When I was a child, I read fairy stories indiscriminately, in collections like The Pink Fairy Book, and did not at first distinguish between authored tales and traditional ones – I was just greedy. I think one of my earliest discoveries that went to making me a writer, was that Hans Andersen was an author, with his own purposes and intents, one of which I was deeply shocked, was to make me, the reader, disturbed and unhappy. Reading ‘The Little Mermaid’ with its agony, and its unsatisfactory, un–fairy–tale ending, disturbed me deeply but I couldn’t avoid it, I knew it was good and important, I kept going back to it. The same was true of ‘The Snow Queen’. It is true that this has a happy ending – but it also has real fear and pain, a real sense of alienation when Kay is the prisoner of the beautiful Snow Queen.

The characters are characters, with passions – including the wonderful robber–girl, who would not have had any character in a true fairy story. Andersen is playing with the counters of the true tale – the glitter of ice and slivers of broken mirror, the quest to find the lost and stolen brother, the witch who catches Gerda, the animal helpers, the magic journey, the magic word that releases the prisoner in the ice palace. But everything in Andersen has feelings, has individuality, is briefly completely alive.

It is true – and this is something that bothered me as a child, that he can be sentimental and moralising. Reading him is difficult – something too sweet is laid over a real apprehension of cold, threatening and frightening things. Through finding what I did and didn’t love in him, I saw more clearly the power of the anonymous tales that simply tell themselves, in their bright, inevitable world.

The tales affirm that courage and persistence will always be rewarded, that a generous spirit has nothing to fear. Andersen knew better. He wrote fairy stories and understood tragedy and terror. We need both. Which is why an eclectic collection like this is such a pleasure to read through.

This is an edited version of A. S. Byatt’s introduction to this edition of The Pink Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang.