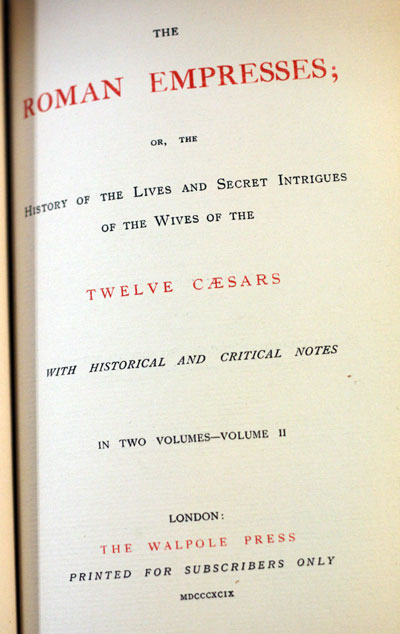

Whilst the Republic of Rome maintained her liberties, the Roman ladies were not distinguished one from another but by their beauty and wit, their virtue and their courage. As they were excluded from dignities, it was only by their personal merit that they made themselves considerable, and acquired glory. Lucretia got herself a great name by her chastity in giving her husband, at the expense of her life, an heroic instance of her innocence;and, in the vengeance which she took on herself for the crime of Tarquin’s son, she left the ladies a model of conjugal fidelity, which we do not find that many have afterwards copied. Cloelia and her companions made themselves famous for their courage, boldness, and love for their country, as did Porcia, Cato’s daughter, by swallowing burning coals, in order to procure to herself that death which her friends would have hindered her from; but she deceived the vigilance of those who watched her, by that action which has made so much noise in history. But, from the time that the Emperors made themselves absolute masters of the Republic, their wives shared with them their grandeur, their glory, and their power; the Roman people, being then given up to flattery as much as they had formerly been jealous of their liberty, strove to give the Empresses pompous and magnificent titles, and to decree them extraordinary and excessive honors. One might then see the Emperors’ wives honored with the titles of August and Mothers of their Country. Some of them had a seat in the senate, governed Rome and the Empire, gave audience to the ambassadors, and disposed of posts and employments; others were consecrated priestesses, and even exalted to the rank of goddesses. It is of these Empresses that this book treats; and particular care has been taken to distinguish those who were of, or who were married into, Augustus’s family, because they were the most remarkable.

All the facts here reported are taken from original authors; and, for our justification, as much care as possible has been taken throughout, to quote our authorities. In speaking of the Empresses, it would to be sure have been very difficult to be quite silent as to the Emperors; I have even enlarged upon some of these princes, because I do not doubt but many, who may peruse this book, will not be at all sorry to find in it a part of their history. If I have not mentioned all that might have been said of these Empresses, I believe I have, at least, reported as much as was necessary to make them known. To say the truth, I have been sometimes almost tempted to suppress a great many things which I have, nevertheless, been obliged to touch upon, but yet with all the regard to decency a man can have, who would be extremely sorry to offend against the rules of good manners. But I hope that nobody will have any great reason to blame me upon that subject, since, even in the most shameful passages of these Empresses’ lives, I have carefully avoided making use of any shocking expressions: I choose rather to be a little obscure in some places, than to explain too well the meaning of the author by an over faithful translation.

– from the preface