About Kapila (from wikpedia):

Kapila (Hindi: कपिल ऋषि) is the founder of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy. Kapila of Samkhya fame is considered a Vedic sage.

Rishi Kapila is credited with authoring the influential Samkhya-sutra, in which aphoristic sutras present the dualistic philosophy of Samkhya. Kapila’s influence on Buddha and Buddhism have long been the subject of scholarly studies.

Many historic personalities in Hinduism and Jainism, mythical figures, pilgrimage sites in Indian religion, as well as an ancient variety of cow went by the name Kapila.

About Sankhya philosophy(from wikpedia):

Samkhya or Sankhya (Sanskrit: सांख्य, IAST: sāṃkhya) is one of the six āstika schools of Hindu philosophy. It is most related to the Yoga school of Hinduism, and it was influential on other schools of Indian philosophy. Sāmkhya is an enumerationist philosophy whose epistemology accepts three of six pramanas (proofs) as the only reliable means of gaining knowledge. These include pratyakṣa (perception), anumāṇa (inference) and śabda (āptavacana, word/testimony of reliable sources). Sometimes described as one of the rationalist school of Indian philosophy, this ancient school’s reliance on reason was neither exclusive nor strong.

Samkhya is strongly dualist. Sāmkhya philosophy regards the universe as consisting of two realities; puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter). Jiva (a living being) is that state in which puruṣa is bonded to prakṛti in some form. This fusion, state the Samkhya scholars, led to the emergence of buddhi (“intellect”) and ahaṅkāra (ego consciousness). The universe is described by this school as one created by purusa-prakṛti entities infused with various permutations and combinations of variously enumerated elements, senses, feelings, activity and mind. During the state of imbalance, one of more constituents overwhelm the others, creating a form of bondage, particularly of the mind. The end of this imbalance, bondage is called liberation, or kaivalya, by the Samkhya school.

The existence of God or supreme being is not directly asserted, nor considered relevant by the Samkhya philosophers. Sāṃkhya denies the final cause of Ishvara (God). While the Samkhya school considers the Vedas as a reliable source of knowledge, it is an atheistic philosophy according to Paul Deussen and other scholars. A key difference between Samkhya and Yoga schools, state scholars, is that Yoga school accepts a “personal, yet essentially inactive, deity” or “personal god”.

Samkhya is known for its theory of guṇas (qualities, innate tendencies). Guṇa, it states, are of three types: sattva being good, compassionate, illuminating, positive, and constructive; rajas is one of activity, chaotic, passion, impulsive, potentially good or bad; and tamas being the quality of darkness, ignorance, destructive, lethargic, negative. Everything, all life forms and human beings, state Samkhya scholars, have these three guṇas, but in different proportions. The interplay of these guṇas defines the character of someone or something, of nature and determines the progress of life. The Samkhya theory of guṇas was widely discussed, developed and refined by various schools of Indian philosophies, including Buddhism. Samkhya’s philosophical treatises also influenced the development of various theories of Hindu ethics.

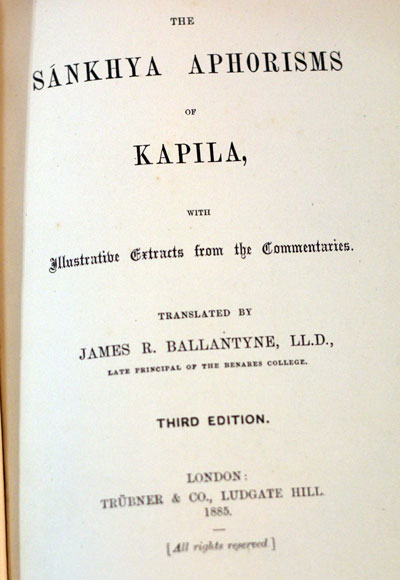

Preface:

The great body of Hindu Philosophy is based upon six sets of very concise Aphorisms. Without a commentary, the Aphorisms are scarcely intelligible; they being designed, not so much to communicate the doctrine of the particular school, as to aid, by the briefest possible suggestions, the memory of him to whom the doctrine shall have been already communicated. To this end they are admirably adapted; and, this being their end, the obscurity which must needs attach to them, in the eyes of the uninstructed, is not chargeable upon them as a fault.

For various reasons it is desirable that there should be an accurate translation of the Aphorisms, with so much of gloss as may be required to render them intelligible. A class of pandits in the Benares Sanskrit College having been induced to learn English, it is contemplated that a version of the Aphorisms, brought out in successive portions, shall be submitted to the criticism of these men, and, through them, of other learned Bráhmans, so that any errors in the version may have the best chance of being discovered and rectified. The employment of such a version as a class-book is designed to subserve, further, the attempt to determine accurately the aspect of the philosophical terminology of the East, as regards that of the West.

These pages, now submitted to the criticism of the pandits who read English, are to be regarded as proof-sheets awaiting correction. They invite discussion.